The John R. Drish House

The Drish House, one of the first plantation homes in the city of Tuscaloosa, sits vacant today. Throughout its history the Drish House has been home to many different people and businesses. At its height it would have been one of the finest homes in Alabama, with views that reached the Black Warrior River and a property spanning more than 400 acres.[1] Built in 1837 by Dr. John Drish, a prominent physician who moved to Tuscaloosa with his new wife and daughter from a previous marriage, the house was originally named Monroe Place. The area surrounding the house has urbanized over time; the formerly oak lined tree entrance (now Seventeenth Street) has developed into businesses and industrial spaces.[2] The house was built by artisan slaves but designed with the help of Dr. Drish himself.[3] Drish enjoyed architecture and is credited for influencing the plans and building of much of early Tuscaloosa, as well as providing labor for the development of the area in his practice of leasing out his enslaved craftsmen.[4] Drish was what architectural historians refer to as a gentleman architect, in that his interest and practice of architecture was a hobby for the doctor. This interest was common for wealthy men during eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Drish acquired his wealth by investing in the early North West- South West Railroad as well as operating a cotton mill in Tuscaloosa; he did not practice medicine after his move to Tuscaloosa.[5]

History and Function

Historians believe the Drish House was a show place of the many styles of work Drish’s slaves could create.[6] It is believed that Monroe Place was so elaborate, both in its exterior and interior designs, to show potential customers what his slaves could do. Drish probably showed potential customers around Monroe Place, pointing out the different styles of work his slaves could complete.[7] From earlier reports it is known that the house was embellished and decorated in every room with custom plasterwork and woodwork.[8] Grand crown molding would have adored every ceiling and doorway.[9] Woodwork would have been painted in the faux woodwork style, which was a practice of painting over the natural wood grains found in wood to mimicking wood grains.[10] This practice, unusual to interior design today, was a way of being obnoxiously wasteful with one’s money by repeating wood grain in paint over the original, natural wood grains. Faux wood gaining is just one example illustrating the amount of wealth in the antebellum South and the elite lifestyle slaveholding afforded its population. Among his enslaved, Drish owned talented woodcarvers, plaster workers and ironworkers.[11]

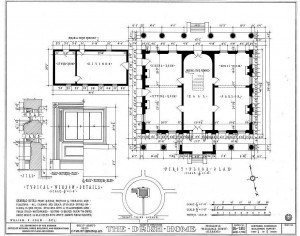

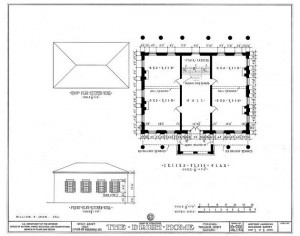

After 1850, Drish dramatically changed the style of his house.[12] Formerly, the Greek Revival house would have been a basic double pile plan with four rooms on each floor (see figure 2).[13] Drish added a tower to the front of the house sometime in the 1850s.[14] With this addition, the style of Monroe Place changed to embody a more Italianate style. While the original double pile floor plan of the main house remained, the tower addition added two more rooms; one room to the second floor and a one roomed-third story in its tower.[15]

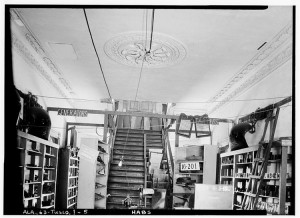

The front door entrance, which stayed in the Greek revival style of the original 1837 house, would have opened to a central hallway foyer. The panel windows surrounding the understated wood framed front door suit the original Greek revival style; a style that placed little emphasis on front doorways.[16] The front two parlor rooms, to the left and right, would have had doors leading from the hallway into each, as well as a doorway into the back parlor rooms. The central hallway continued to reveal an elaborate wrought iron-railed double staircase, now replaced with a much less elaborate wooden double staircase.[17] The wrought iron railing work was repeated on the exterior railings on the additions of the second story balconies (see figure 8). The balcony around the second story exists only in pictures, with no mention to when this addition was made. The exact placement period of the balconies support beams off of the exterior are unknown, and the exterior was plastered over when the balcony was removed.[18] As a result, historians only have old photographs of the balcony when it was in place as their clues to try and determine the depth of the structure. Historians are unsure if the balcony extended the entire perimeter of the second story or if the balcony stopped, including only the front and two sides and excluding the back entrance.[19] The addition of the second story balcony created a covered wrap around porch for the first floor. It is also unclear if second story tower room had doors leading out to the balcony. The tower repeated the iron work of the balcony railings surrounding its top story room, creating a faux third story balcony. The kitchen, which has since been demolished, was separate from the main house; typical of house design of the nineteenth century (see figure 8).[20] With the addition of the second story balcony, the kitchen, seen in pictures to the left of the main façade, had a covered walkway to and from the house.

The Tuscaloosa County Preservation Society has found what is likely the original carpet pattern and fabrics used in the house by going through John Drish’s correspondences regarding interiors.[21] Using those letters, historical preservationists were able to determine what patterns the made-to-order hand whelped carpets were designed in. Even though the houses’ floors were covered in hard wood, carpeting was more expensive and thus reserved for only the finest houses.[22] Going through Drish’s company archives, preservationists found the designs available during that time period.[23] Using the colors mentioned in Drish’s letters as their clues, they were able to identify the patterns of carpet in the original Monroe Place house.[24] The carpet designs would have been three different patterns; a one for each room of the first floor, in the colors black, dark grey and orange.[25] These carpets, only seen in the finest homes due to the exorbitant cost of hand warped designs, would have adorned the floors in the parlor rooms of the first floor and central hall.[26] The exact carpet patterns are still manufactured today and could be made to restore the house to its original grandeur.

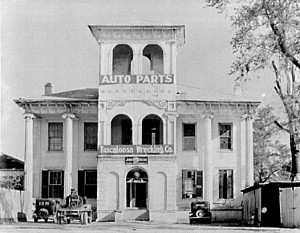

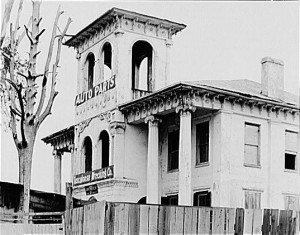

Having survived the Civil War, John Drish died in 1867, leaving the house to his second wife Sarah.[27] Unfortunately, with his death went the wealth of the Drish family. Sarah died penniless, yet her house slaves stayed with her caring for the house until her death in 1884.[28] After the Drish’s occupancy, records show the house being owned by a Colonel (exact date unknown), then the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Light Company.[29] The Board of Education took ownership in 1906, using the house as the Jamison school and adding the brick building that can be seen to the right of the original house plan as an extension of the school (see figure 3).[30] The upstairs floor plan, originally a double pile plan, was also changed as the school divided up and changed the rooms, adding smaller rooms.[31] In 1925 the hands of Monroe Place changed again, as Charles Turner, owner of the Tuscaloosa Wrecking Company, bought the house (see figure 8). During his ownership, the house was used as a ware house for junk automobile parts, seen in the famous photograph (taken 1936) by Walker Evans displayed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art today (see figure 9).[32] In Evans’ photograph, the contrast of a former grand plantation house being used as junkyard for auto parts reflected the demise of the plantation era. In 1940 Monroe Place then passed ownership again to the Southside Baptist Church, who abandoned it 1994 for its dilapidated state and threats by the Tuscaloosa Building Council for demolition.[33] The Church left the house to the Heritage Council of Tuscaloosa County in 1995.[34] The house sat virtually untouched until 2006 when it was deeded over to the Tuscaloosa County Preservation Society with plans to restore the house to its former glory.[35] In 2009, the Jamison school addition, built in 1906 was demolished (see figure 4).[36] The demolition restored the house to its original plan, but the cost of demolition consumed the Preservation Society’s budgeted funds to start the restoration process.[37]

When the Baptist Church took ownership, the elaborate plasterwork, created by the skilled artisan slaves, was torn down to further fit the style of a Baptist church.[38] The plasterwork, nearly 100 years old when the church took ownership in 1940, survived throughout the many changes of hands and functions of the former grand domestic house (see figure 5). Unfortunately, any remaining plasterwork was torn down by the Baptists, as their religion calls for no ornamentation.[39] But all was not lost for preservationists as some of the plasterwork can be seen in old photographs and in the third story tower room.[40] If preservation efforts included restoring the plasterwork, which is only appropriate as Monroe Place was known for its accomplished plasterwork, are to be completed, the remaining intact crown molding plaster sections still attached on the ceilings of the third floor tower room could be used as a reference to replicate the design the enslaved craftsmen created.[41]

The grand marble and cast iron staircase that is said Drish fell off to his death has been replaced by a less grand wooden double staircase. The exact date of this change is unknown. The original staircase plan and remains of where the cast iron bars attached to the walls can be seen on the interior brickwork, hidden in a closet today, another addition from the original house plan.[42] Along with the destruction the Church did to the plasterwork and moldings, the Baptist church painted the originally white house the pink color it remains in today.[43]

Today, Tuscaloosans recognize the Drish house as one of the most haunted sits of Alabama. The original slave-created ornamentation that made the house one of the finest in Tuscaloosa and influential in the areas architecture has vanished from the façade. The house is a bare bones model of its original grandeur. Now boarded up and closed to the public, the house sits waiting for its repairs.

Style

John R. Drish built Monroe Place in the early Greek Revival style in 1837. The house fits the basic model of a Greek style house as it is built upon a pedestal, symmetrical on every façade and square in its plan (see figure 2).[44] Design elements of the Drish House characteristic of the Greek Revival style are the four ionic columns, two on each side, of the main façade tower (the tower a later addition added in the 1850s) (see figure1). The back façade has a series of 6 Doric order columns, extending the entire length of the house from pediment to roofline (see figure 6). The house is made of brick and plastered over to create a smooth façade, a design element attributed to the Greek revival style of smooth exteriors resembling marble of ancient Greek architecture. The original building exterior would have been painted white.[45]

The interior floor plan, the double pile, is characterized by two similarly sized rooms on either side, separated by central hall, where the staircase leads to the second floor with a matching floor plan.[46] Consistent with the interior floor plan is the two entrances- a front and a back, an element common in the double pile plan.[47] Characteristic to country or plantation houses built at this time, one entrance would open up to the front lawn where guests would enter.[48] Today, this is the side with the tower and still seen as the main façade of the house. Originally, the street that would lead up to the main entrance would have been lined with oak trees.[49] The Drish’s property would have originally extended in the front towards where Fifteenth Street meets Seventeenth Street today.[50] A small building would have been built at the end of the oak lined entrance, marking the start of the Drish’s property and acting as somewhat of a security gate for the Plantation.[51]

The back entrance of Monroe Place opened up to the acres of land Drish owned.[52] The back façade would have been seen mainly by the slaves or the Drish’s themselves.[53] The back façade features six Doric columns. Before the tower addition, the two façades would have looked similar in their design of a columned pedestaled porch, with the only difference being that the back columns were Doric and the front columns were in the Ionic order.

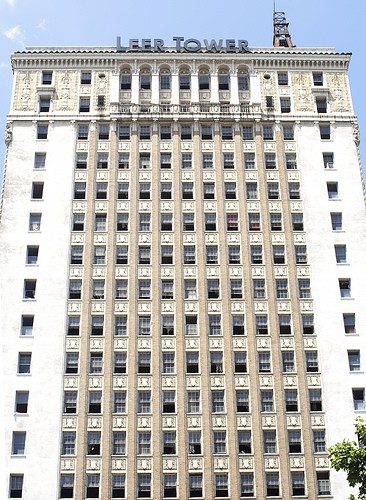

The addition of the three story tower on the main façade side in the 1850s consumed two of the six ionic columns of the original Greek revival design (see figures 8 and 11).[54] This addition distinguised the front façade from the back, marking the front as the main entrance, much grander and more elaborate than the original Greek Revival style of the back. The addition of a three story front tower enclosed the main front door in a portico, elements that more closely resemble the Italianate architectural design style.[55] Towers originate to the Italianate style as they were traditionally added to the houses of the wealthier Italians as a security measure.[56] The function of the tower at Monroe Place and John Drish’s motive for its addition are unclear to historians today, but local tale tells of a neighboring plantation constructing a tower addition to its design.[57] Thus, Drish constructed his tower in competition in an effort to keep his house the show place of early Tuscaloosa.[58] The tower added an additional room to the second story of the double pile plan, directly above the main entrance door and extending towards the columns on the front porch. In this additional room, a staircase would lead to the room above, the third story tower room. The highest point of the house, the tower room would reveal the view of the surrounding lands.[59] The tower has rounded arched windows, contrasting to the rectangular windows of the Greek revival style seen on the rest of the house. The widows of the tower would have been iron paned.

During the 1850 remodeling, second story balconies were added with ornate cast iron railings (see figure 8).[60] The exact placement of the balcony extending from the Greek revival style house varies in reports and documents.[61] Some historians believe the balcony extended the entire perimeter of the house and had entrances into the tower room.[62] Photographs show the balcony from the main front façade, but no images exist of back entrance when the balconies were present on the house. The exterior markings of where the balcony would have been attached to the house have been plastered over.[63]

The house was heavily ornamented on the main exterior tower-side with plaster work. Each story of the front tower had a string course on the exterior, showing clear divisions between the three stories. These remaining markings may not be internal design elements, but could be remnants of where the iron work was attached to the house as seen in photographs. At the roofline, the house has carved wooden corbels connecting the walls of the house with the slight extension of the roof, acting as additional decorative support for the building’s roof. Between every corbel are wooden floral appliques, which serve no purpose but decoration. The corbels and floral appliques are repeated on the towers’ roofline. The rounded and arched windows of the tower would have been trimmed with plaster. The windows show slight shadows of the placement of the plastered trim. Faux Corinthian columns, mostly intact, flank either side of the top level tower windows. The middle story tower windows would have originally had faux ionic columns, and the columns’ shaft is still attached to the tower but the ionic bases are gone. The false ionic columns mimic the original full sized ionic columns that extend from the house’s raised pediment porch to the roofline. Nearly all the false columns and plasterwork added to the tower have disappeared with the building’s deterioration, with the exception of remnants of the third story Corinthian columns. No remnants of the original arched windows of the tower remain, but photographs show them being iron paneled.

The wrought iron railings of the second story balcony are mimicked around the highest level of the tower. The roof of the tower was crowned with a metal decorative pole. In later photographs, dark shutters adorn the sides of the houses windows, not a characteristic of the Greek revival or the Italianate design, but more cohesive with the houses original purpose of a plantation home.

The Drish house is unique in Alabama architecture seen through its development of styles and design over time. Built into a Greek Revival style, it was remolded nearly twenty years later to encompass another style of architecture completely, in the Italianate style. The result is a truly unique looking house, with elements true to both styles and well as the original function of the house as a plantation. Because of John Drish’s involvement in the development of early Tuscaloosa, it is reasonable to believe that he continued the decoration and over-ornamentation of his house in an effort to keep up with the popular styles of building at the time and as advertisement for his slaves to builders in the area.[64] The 177 year old house has garnered much attention for its unique appearance; often looking out of place, in a town of nearly all neoclassical architecture.

Historians claim the architecture of the Drish house was influential in early Tuscaloosa architectural development.[65] Yet, contrary to that claim, no other surviving Tuscaloosa area buildings combine different architectural styles onto one as the Drish house did; marrying various styles together onto one façade.[66] The city of Tuscaloosa has built around the Drish House, leaving the formerly celebrated Monroe Place as an omniscient reminder of the once grand plantation economy the South was afforded by slave labor. Today, the Drish house sits in dilapidated state, falling into further decay with each passing day. The house is a skeleton; the bones and original structure of the building still stand, yet most of the ornamentation that made the house unique in the study of architecture have been destroyed. The Drish house is significant for its involvement in the advancements of architecture in Alabama as well as its significance as a former plantation home built and elaborately decorated by slaves. Restoration of this historically important house to its original grandeur as a showcase house of what the artisan slaves could accomplish is possible. The Drish house is owned by the Tuscaloosa Historical Preservation society, who plans to fully restore the house in the future.[67]

Bibliography

Crawford, Ian (member of Tuscaloosa County Preservation Society and historian), in discussion and tour of the Drish house, March 21, 2014.

“Drish house”. Tuscaloosa County Preservation Society. Accessed February 14, 2014. http://www.historictuscaloosa.org/index.php?page=drish-house

“Dr. John H. Drish House, 2300 Seventeenth Street, Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, AL.” Accessed February 14, 2014. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/AL0777/

Hayes, Susan and Suzanne Wolfe. “The Drish House: Haunting Past, Hopeful Future.” Alabama Heritage 91 (2009): 6-7.

Gamble, Robert. The Alabama Catalog: Historic American Buildings Survey/ a Guide to the Early Architecture of the State. University, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1987.

Mellown, Robert O. Historic Structures Report/ The John R. Drish house. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Heritage Commission of Tuscaloosa County, 2001.

Ratcliff, Eric. “The Williamane in van Diemen’s land: The coming of Italianate architecture.” Papers And Proceedings: Tasmanian Historical Research Association 59, no. 2 (2012).

[1] Susan Hayes and Suzanne Wolfe, “The Drish House: Haunting Past, Hopeful Future,” Alabama Heritage 91 (2009): 6-7.

[2] Ian Crawford, in discussion and personal tour, March 21, 2014.

[3] “Drish House”, Tuscaloosa County Preservation Society, Accessed February 14, 2014.

[4] Robert Gamble, The Alabama Catalog: Historic American Buildings Survey/ a Guide to the Early Architecture of the State (University, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1987), 78-79.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ian Crawford, in discussion and personal tour, March 21, 2014.

[7] Ian Crawford, in discussion and personal tour, March 21, 2014.

[8] Susan Hayes and Suzanne Wolfe, “The Drish House: Haunting Past, Hopeful Future,” Alabama Heritage 91 (2009): 6-7.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ian Crawford, in discussion and personal tour, March 21, 2014.

[11] Susan Hayes and Suzanne Wolfe, “The Drish House: Haunting Past, Hopeful Future,” Alabama Heritage 91 (2009): 6-7.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “Dr. John H. Drish House, 2300 Seventeenth Street, Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, AL,” February 14, 2014, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/AL0777/.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Robert Gamble, The Alabama Catalog: Historic American Buildings Survey/ a Guide to the Early Architecture of the State (University, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1987), 78-79.

[17] Ian Crawford, in discussion and personal tour, March 21, 2014.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] “Dr. John H. Drish House, 2300 Seventeenth Street, Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, AL,” February 14, 2014, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/AL0777/.

[21] Ian Crawford, in discussion and personal tour, March 21. 2014.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Susan Hayes and Suzanne Wolfe, “The Drish House: Haunting Past, Hopeful Future,” Alabama Heritage 91 (2009): 6-7.

[28] Ian Crawford, in discussion and personal tour, March 21, 2014.

[29] “Dr. John H. Drish House, 2300 Seventeenth Street, Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, AL,” February 14, 2014, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/AL0777/.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] “Drish House”, Tuscaloosa County Preservation Society, Accessed February 14, 2014, http://www.historictuscaloosa.org/index.php?page=drish-house.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ian Crawford, in discussion and personal tour, March 21, 2014.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Robert Gamble, The Alabama Catalog: Historic American Buildings Survey/ a Guide to the Early Architecture of the State (University, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1987), 78-79.

[45] Ian Crawford, in discussion and personal tour, March 21, 2014.

[46] “Dr. John H. Drish House, 2300 Seventeenth Street, Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, AL,” February 14, 2014, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/AL0777/.

[47] Robert Gamble, The Alabama Catalog: Historic American Buildings Survey/ a Guide to the Early Architecture of the State (University, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1987), 78-79.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ian Crawford, in discussion and personal tour, March 21, 2014.

[50] “Dr. John H. Drish House, 2300 Seventeenth Street, Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, AL,” February 14, 2014, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/AL0777/.

[51] Ian Crawford, in discussion and personal tour, March 21, 2014.

[52] “Dr. John H. Drish House, 2300 Seventeenth Street, Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, AL,” February 14, 2014, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/AL0777/.

[53] Robert Gamble, The Alabama Catalog: Historic American Buildings Survey/ a Guide to the Early Architecture of the State (University, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1987), 78-79.

[54] Ian Crawford, in discussion and personal tour, March 21, 2014.

[55] Eric Ratcliff, “The Williamane in van Diemen’s land: The coming of Italianate architecture,” Papers And Proceedings: Tasmanian Historical Research Association 59, no. 2(2012).

[56] Ibid.

[57] Susan Hayes and Suzanne Wolfe, “The Drish House: Haunting Past, Hopeful Future,” Alabama Heritage 91 (2009): 6-7.

[58] Ibid.

[59] “Drish House”, Tuscaloosa County Preservation Society, Accessed February 14, 2014, http://www.historictuscaloosa.org/index.php?page=drish-house.

[60] Ian Crawford, in discussion and personal tour, March 21, 2014.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Robert Gamble, The Alabama Catalog: Historic American Buildings Survey/ a Guide to the Early Architecture of the State (University, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1987), 78-79.

[66] Ibid.

[67] “Drish House”, Tuscaloosa County Preservation Society, Accessed February 14, 2014, http://www.historictuscaloosa.org/index.php?page=drish-house.