The Gorgas House

Tuscaloosa, Alabama

Built 1829

By: Madison Leavelle

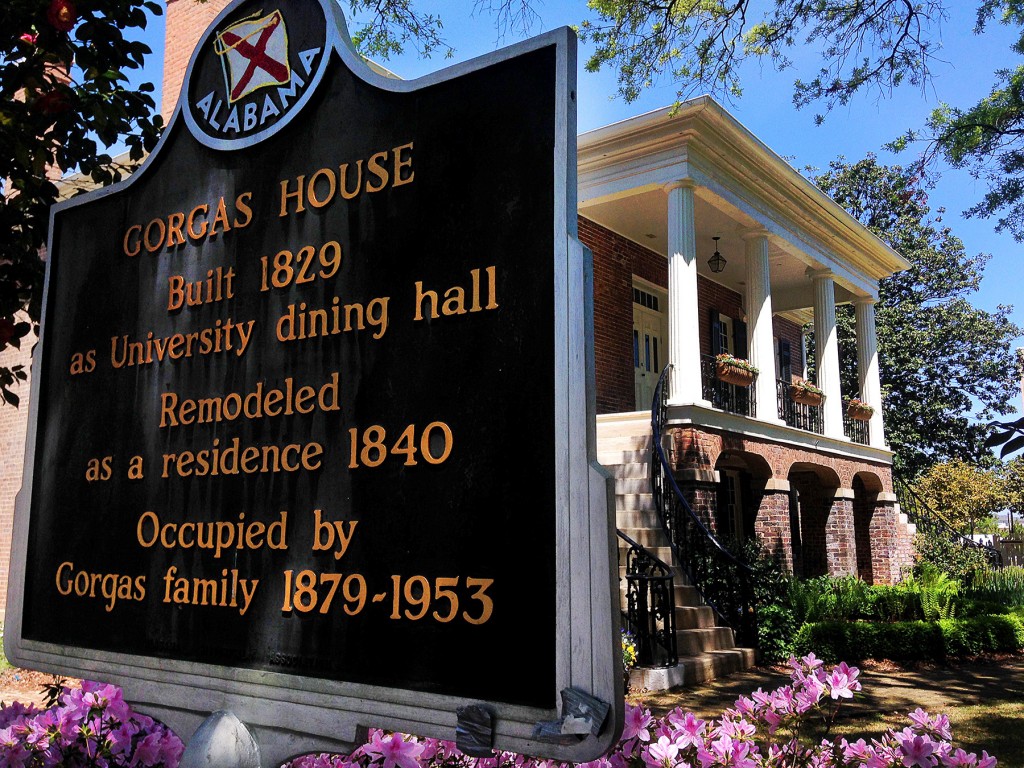

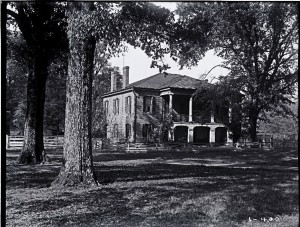

The Gorgas House (fig.1), located on the University of Alabama campus in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, was built in 1829. Not only is it considered to be the first permanent housing structure on campus,[1] but it is also the only surviving structure on campus that assimilated the original University of Alabama campus design.[2] The site of the University of Alabama’s campus sits on a plot of land that was once called “Marr’s Plantation.”[3]

According to the Library of Congress’s Historical Building Survey, the Gorgas House was “erected on the site of the cabin of the original squatter (Marr).”[4] In 1827, a board of trustees allowed construction on the campus to begin. English architect, William Nichols, (1780-1853) provided the original plans for the site. Nichols, who was also the state architect at the time, was already living in Tuscaloosa and was overseeing the construction of the his newly designed State Capitol building. Taking a few key elements from his statehouse design, Nichols devised a plan for the college site that made use of a “Classical Revival” theme. Alabama’s campus design was also influenced by Thomas Jefferson’s scheme for the University of Virginia and, therefore, upheld the Jeffersonian ideal in architecture, which was very popular at this time.[5] William Nichol’s designed the Gorgas Home with the intent of it being a dining hall. The first floor of the building, or “Steward’s Hall” as it once was called, served as the refectory and the main steward lived upstairs.[6] Nichol had originally planned for a second “Steward’s Hall” to go on the eastern side of campus, but it was determined that it was too difficult to manage two dining halls. [7] Other documents state that the Gorgas House was also known as “The Hotel” and provided a common area for students.[8] Some fifteen years after it was built, in 1829, , the structure was renovated and remodeled in order to serve as a faculty residence. Despite the fact that the upstairs was a residence, the university sometimes used the ground floor area as a classroom.

Around 1860, the president of the University of Alabama, President Landon Cabell Garland, began to inaugurate a new resolution for the school that eventually switched the campus from being a place of higher learning and into a type of military governed school. Rumors and talks of secession from the North helped to recruit young men who wanted to be prepared if war was ever declared. Once the war broke out, the school had a hard time with student enrollment and keeping students at the school. Many left to serve in the Confederate forces.[9] In April 1865, Major General James H. Wilson of the United States Army led 14,000 soldiers into the state of Alabama in hopes of destroying anything deemed useful to the Confederacy and its armies. Their main focus was to defeat Lt. Gen. Nathaniel Bedford Forrest, destroy any iron or textile manufactories, demolish the arsenal and capture the state capitol, Montgomery. Along their route, Wilson unexpectedly changed his original invasion plans. His new goal was to head to Selma and destroy the main military manufacturing centers, but he discovered the quickest way was to travel through Tuscaloosa. On April 3, 1865, the Yankee troops invaded the city of Tuscaloosa. Although the University’s cadets were small in number, they held the opposing forces as best they could. The Yankee troops were victorious and officially captured the town on April 4. Under orders, soldiers were told to burn the University’s public buildings. Only four buildings survived the fire: the President’s Mansion, the Observatory (Maxwell Hall), the Little Round House, and the Gorgas Home. According to some first hand accounts, “Steward’s Hall” (Gorgas House) and the Observatory building evaded the attack because Mrs. Reuben Chapman, a wife of a former Alabama governor who happened to live nearby, persuaded one of the Yankee officers to not burn them. She told him that the two buildings “had in no way contributed to the spirit of the rebellion in the South.”[10] It was also documented that one of the last classes held on campus the day of the invasion was actually held in the Gorgas House. The faculty member who lived upstairs in the house at the time was Professor John Wood Pratt, who held his “two o’clock oratory and rhetoric class” in the downstairs dining room. The student wrote that Pratt was having trouble keeping the class focused and ultimately let the class out early. [11]

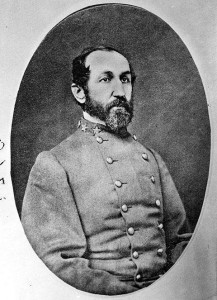

The Gorgas House gets its name from its most famous residents, the Gorgas Family. Josiah Gorgas (1818-1883) [fig.2]

was a Northern-born Confederate General during the Civil War, and was eventually the University of Alabama’s seventh president (fig.2). He was born in Pennsylvania to a middle class Dutch family. He entered into the U.S. Military Academy when he was nineteen years old. He graduated sixth in his class from West Point in the Ordnance Corps. He was sent to Mobile, Alabama to work on the reconstruction of a fort, and it was there that he met Amelia Gayle, his future wife. They were married soon afterward. Although not much is said on why Gorgas chose to side with the Confederacy instead of the Northern U.S. Army, many speculate that it was because of his newly established Southern familial ties. During the war, Gorgas served as a chief ordinance, managing the Confederate army’s arsenals, armories, and ammunitions. After the war, he was offered a teaching job at the University of the South in Tennessee. His health began to decline and was forced to resign. Close family friends were able to get him the job of President of the University of Alabama in 1878, but after a year of serving in the position, his health was severely in decline and thus had to resign once more.[12] The Board of Trustees gave him the Gorgas house as a retirement present and gave him the position of Head Librarian. General Gorgas died in 1883.[13]

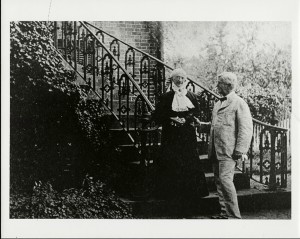

Amelia Gayle Gorgas (fig.3) was the daughter of John Gayle (1792-1859), a former Governor of Alabama. She married her husband, General Josiah Gorgas, in 1853 and together they had six children. When her husband resigned as the President of Alabama due to declining health and was given the role of Librarian, Amelia was also offered the position of matron of the University Infirmary and postmistress.[14] From about 1888 to 1907, the post office was located on the ground floor of the house. The infirmary was also located in the house.[15] After her husband’s death in 1883, she quickly took on his role as Head Librarian, expanding the library from 6,000 books to 12,000 volumes. She served as librarian until 1906 and she passed away in 1913. The main library on campus, the “Amelia Gayle Gorgas Library” is named in her honor.[16] Her son, William Crawford Gorgas (fig.3) (1854-1920), is most famous for finding and reducing the cause of Malaria and Yellow Fever in Panama. He was also the Surgeon-General of the United States Army from 1914 until his death. [17] The Gorgas family is buried in Evergreen Cemetery (connected to Calvary Baptist Church near University of Alabama campus), with the exception of William, who is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

After the death of Amelia in 1913, her daughters continued to live in the home and help in the library. In 1944, the house was dedicated as a memorial to the Gorgas family, by the Alabama State Legislature and was officially titled, “the Gorgas House.” The University allowed the sisters to continue to live in the house. In 1953, the last Gorgas child passed away. The Gorgas home was transformed into a museum and it currently stills functions as such.[18]

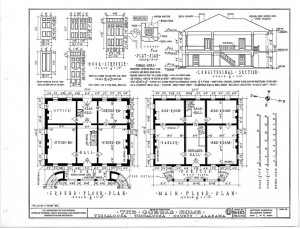

The Gorgas House has changed in its appearance over the years. It is currently in the Greek Revival style. In 1829, Nichol’s original campus plan followed a Jeffersonian or Neoclassical aesthetic that was also played out into the original Gorgas House design.[19] The Federal style has also been used to describe the house’s architectural features, but only when it is discussed sans front portico.[20] Some experts have said that the general style is of a “low-country raised cottage.” Nichol’s, in fact, liked the visual elegance of the elevated, high basement look.[21] This style was commonly used in colonial architecture found in Louisiana and South Carolina. This architectural style was popular in those areas because it was very practical for its environment. By raising the principal rooms of the house to a story above the ground floor, it created distance from the damp soil.[22] It would make sense that Nichol’s would choose this version of architecture since he was the State Architect of the Carolinas for a period of his life, and thus, he would have been very familiar with this type of building. [23] When the building functioned as the dining hall, the main portion of the first (lower) floor was one, very large room with fireplaces on each end of the house. When it was renovated into a private residence in the 1840’s, partitions, or walls, were placed into the bottom floor. This divided the floor into a central entrance hall, with a living room and a dining room on either side. The staircase in the central entrance hall was also added at this time. The kitchen was detached from the house and sat on the site where Morgan Hall currently resides. It was a two-stories and it was said to have been older than the Gorgas house although there is no documentation to prove it otherwise. In 1853 the front porch was added to the façade of the house. Originally, the portico was built with having only one arch (fig.4), but in 1896 the porch was expanded to its current size (fig.5). On the interior, the finishes on the walls were originally a hard-finish white plaster. Another Carolina-inspired architectural feature brought in by Nichols was the woodwork had been painted white. Nichols used this aesthetic in several of his buildings.

The added portico in the 1890s was most likely a reaction to the popular building styles in the South during this time. By adding the porch, the Gorgas House became increasingly more identifiable with the Greek revival style. The house is a rectangular shape with a double pile layout. It has two stories, including an attic, but no basement was dug. The central hallway, on the first floor of the building, has two large rooms off either side (the dining room and sitting room) with two smaller rooms in the back of the house (the office and a serving room) off of what was a rear hallway. The second floor has two bedrooms and one master bedroom, as well as a parlor room (fig.6).[24] The four columns on the upper level part of the portico are Doric columns that sit on top of four flattened Romanesque arches.[25] One of the most striking features of the building is its double curved cast iron stairs on the exterior of the house (fig.7). [26] The house has four chimneys in total with two on each side of the house. The Gorgas home also has large paned windows. The house has a low gable and hipped roof.[27] It is completely made out of red brick and is laid using the Flemish Bond. The walls are about eighteen inches thick. When it was originally constructed, it was built almost entirely without using nails. The structure was placed together using a mortised and pegged type of assembly.[28]

The Greek revival style was most popular during the early nineteenth century, specifically from 1820s to 1860s. During this time, America was really developing itself politically, expanding its territory, and establishing itself as a real power. There was undoubtedly a strong sense of confidence in the United States at this time and the American people felt that their architecture needed to show this. Trying to separate themselves from England and the English colonial lifestyle, they wanted to have their own identity, so they drew inspiration from the classical world. Thomas Jefferson was interested in the way classical architecture could provide a statement and incorporated it into the nation’s capital buildings. He saw this architecture as a symbol of democracy. This Grecian style for many years was just used just for government buildings, but in the beginning of the nineteenth century, the aesthetic spread to other public buildings, spaces, and banks. Slowly, people started applying it to their homes, although the majority of whom picked this architecture style, were some of the wealthiest people in society.

In Alabama, the Federal style of architecture was more prominent before the Greek revival popularity struck the South. The Federal style drew more from Roman details rather than Greek, but like the Greek Revival Style, it was very particular about details, size, accuracy, and symmetry. Around the 1820s-1830s, Alabama was growing fast—new towns were beginning to spring up and doing financially very well. The influx of new settlers, especially wealthy settlers in merchant towns, in turn created an opportunity for new construction and new, fresh ideas that incorporated a theme of assembling old with the new.[29] The movement from the more conservative types of the Greek style, allowed for a very distinct style of the Greek revival form to thrive. The development of the southern Greek form goes hand in hand with the southern climate. Wealthy southern plantation owners needed a place to cool down on a hot, humid Alabama day. The house plan became more open compared to northern versions of the house. This allowed for better air circulation. The need for a veranda or a full portico was more widely used in the South because the need to be shaded from the sun was very important. These house structures were low spreading styles. This meant that the first floor was raised way off the ground. The façade of the houses usually had Greek details, such as columns. They usually had two-story colonnades, but it was not unusual to have a one-storied version. The houses of Alabama, with this version of architecture, blended the perfect amount of practicality, domesticity, whiles still being very splendid. [30] Some other characteristics of the Greek Revival style included a symmetrical façade, was of rectangular shape, a full width portico, entablatures with low pitched roofs above them, as well as pilasters and balustrades. The people of the South made the Greek revival style its own. They adapted their designs to accommodate the climate of the southern states, while simultaneously creating a glamorous view of the antebellum period. [31]

—————————————————————————————————————

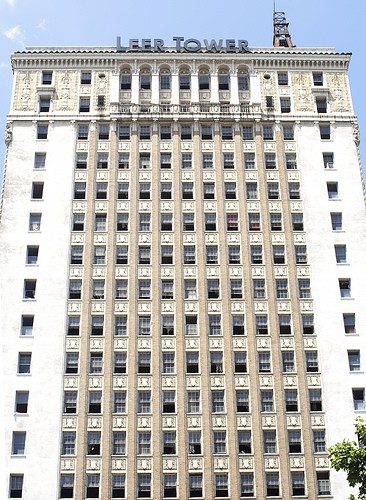

The Gorgas House has had ALOT of influence on some of the architecture around the city of Tuscaloosa. Here are some buildings in town that have used aspects of the Gorgas Home in their structures:

My parents got married at the Gorgas House in 1983. Here are a few photos of their wedding at the historic home:

—————————————————————————————————————-

Footnotes:

[1] “Gorgas House: On the Campus of the University of Alabama.” brochure, University of Alabama, pg. 1.

[2] Robert Oliver Mellown, The University of Alabama: A Guide to the Campus and Its Architecture [Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 2013], pg.54.

[3] “Gorgas House: On the Campus,” pg. 1.

[4] Library of Congress, “University of Alabama, Josiah Gorgas House, Ninth Avenue & Capstone Drive,” Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey, http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/al/al0700/al0789/data/al0789data.pdf.

[5] Robert Oliver Mellown, pg. 1-5.

[6] “Gorgas House: On the Campus,” pg.3.

[7] Robert Oliver Mellown, pg.55.

[8] Library of Congress , Historic American Buildings Survey online.

[9] Robert Oliver Mellown, pg. 5-6.

[10] William Stanley Hoole and Elizabeth Hoole MacArthur, The Yankee invasion of West Alabama, March-April, 1865: including the Battle of Trion (Vance), the Battle of Tuscaloosa, the Burning of the University, and the Battle of Romulus [Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Confederate Pub. Co., 1985], pgs. 7-35.

[11] Robert Oliver Mellown, pg. 55-56.

[12] Charles F. Ritter and Jon L. Wakelyn, Leaders of the American Civil War: A Biographical and Historiographical Dictionary [Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press,1998], pg. 146-151.

[13] Robert Oliver Mellown, pg. 57.

[14] Robert Oliver Mellown, pg. 57.

[15] Library of Congress, Historic American Building Survey online.

[16] “Gorgas House: University of Alabama: Souvenir Booklet.” brochure, University of Alabama, 1980. pg. 8.

[17] “Gorgas house: On the Campus,” pg. 5.

[18] Robert Oliver Mellown, pg. 57.

[19] Robert Oliver Mellown, pg. 2-3.

[20] National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, Gorgas-Manly Historic District, Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, N.R. #71000108.

[21] Clay Lancaster, Greek Revival Architecture in Alabama [Montgomery: Alabama Historical Commission, 1977], pg. 1-4.

[22] “Gorgas House, University of Alabama: Souvinr Booklet.” pg. 2.

[23] Robert Oliver Mellown, pg. 3.

[24] “Gorgas House: On The Campus, pg. 2-3.

[25] National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, Gorgas-Manly Historic District.

[26] Library of Congress, Historic American Bilding Survey online.

[27] Historic American Buildings Survey: Catalog of the Measured Drawings and Photographs of the Survey in the Library of Congress, March 1, 1941, [Washington: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, 1941].

[28] “Gorgas House: University of Alabama: Souvenir Booklet.” Pg. 1-10

[29] Clay Lancaster, pg. 3.

[30] Talbot Hamlin and Sarah Hull Jenkins Simpson Hamlin, Greek Revival Architecture in America: Being an Account of Important Trends in American Architecture and American Life Prior to the War Between the States [London: Oxford University Press, 1944], pg. 202-212.

[31] Cheryl Morgan and Marjorie Longenecker White, A Guide to Architectural Styles featuring Birmingham Homes [Birmingham: Birmingham Historical Society, 2003], Pg. 7.

—————————————————————————————————————-

Bibliography

“Gorgas House: On the Campus of the University of Alabama.” brochure, University of Alabama, 1975.

“Gorgas House: University of Alabama: Souvenir Booklet.” brochure, University of Alabama, 1980.

Amelia Gayle Gorgas and William Crawford Gorgas on steps of Gorgas Home. 1900. William Stanley Hoole Special Collections Library, University of Alabama Collection, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The University of Alabama Libraries Digital Collection. Web http://purl.lib.ua.edu/57065/.

Amelia Gayle Gorgas Standing in Front of Her House. 1910. William Stanley Hoole Special Collections Library, University of Alabama Photograph Collection, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The University of Alabama Libraries Digital Collection. Web http://purl.lib.ua.edu/91731/.

Downstairs Hallway, Gorgas House. 1960. William Stanley Hoole Special Collections Library, University of Alabama Collection, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The University of Alabama Libraries Digital Collection. Web http://purl.lib.ua.edu/54836/.

Gamble, Robert S. Historic Architecture in Alabama: A Guide to Styles and Types, 1810-1930. 1 ed. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: Univ. of Alabama Press, 2002.

Gamble, Robert S. The Alabama Catalog: Historic American Buildings Survey: A Guide to the Early Architecture of the State. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 1987.

Gorgas House 1897. 1897. William Stanley Hoole Special Collections Library, University of Alabama Photograph Collection, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The University of Alabama Libraries Digital Collection. Web. http://purl.lib.ua.edu/455568/.

Hamlin, Talbot, and Sarah Hull Jenkins Simpson Hamlin. Greek Revival Architecture in America: Being an Account of Important Trends in American Architecture and American Life Prior to the War Between the States, London: Oxford University Press, 1944.

Historic American Buildings Survey: Catalog of the Measured Drawings and Photographs of the Survey in the Library of Congress, March 1, 1941. 2nd ed. Washington: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, 1941.

Hoole, William Stanley, and Elizabeth Hoole McArthur. The Yankee Invasion of West Alabama March-April, 1865: including the Battle of Trion (Vance), the Battle of Tuscaloosa, the burning of the University, and the Battle of Romulus. University, Ala.: Confederate Pub. Co., 1985.

Lancaster, Clay. Greek Revival Architecture in Alabama. Montgomery: Alabama Historical Commission, 1977.

Library of Congress. “Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey.” University of Alabama, Josiah Gorgas House, Ninth Avenue & Capstone Drive, Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, AL- Written Data. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/al/al0700/al0789/data/al0789data.pdf (accessed April 4, 2014).

Mellown, Robert O. The University of Alabama: A Guide to the Campus. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2013.

Morgan, Cheryl, and Marjorie Longenecker White. A Guide to Architectural Styles featuring Birmingham Homes. Original limited ed. Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Historical Society, 2003.

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, Gorgas-Manly Historic District, Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, N.R. #71000108.

Owen, Thomas McAdory, and Marie Bankhead Owen. History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography, Chicago: S.J. Clarke Pub. Co.,1921.

Ritter, Charles F., and Jon L. Wakelyn. Leaders of the American Civil War: A Biographical and Historiographical Dictionary. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1998.

Robinson, Gus. Upstairs Parlor, Gorgas House. 1955. William Stanley Hoole Special Collections Library, University of Alabama Collection, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The University of Alabama Libraries Digital Collection. Web. http://purl.lib.ua.edu/54802/.

View of Dining Room, Gorgas House. 1955. William Stanley Hoole Special Collections Library, University of Alabama Collection, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The University of Alabama Libraries Digital Collection. Web. http://purl.lib.ua.edu/54816/

View of Gorgas House, University of Alabama. 1890. William Stanley Hoole Special Collections Library, Eugene Allen Smith Collection, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The University of Alabama Libraries Digital Collections. Web. http://purl.lib.ua.edu/46355.

———————————————————————————-