On December 6, 1825, the Alabama State Senate agreed to move the state’s capital, then in Cahaba, to the growing town of Tuscaloosa. The history surrounding Tuscaloosa’s time as State Capitol shows a growing and changing series of events in Alabama’s history. Tuscaloosa began to operate as Alabama’s third state capitol in 1826, until 1846 when Montgomery was chosen as a new, more centralized location.[1] The need for a dedicated capital building that time led the city to commission the English architect William Nichols to work as state architect of Alabama, his first project in his new position to design and oversee the construction of the new State Capitol in Tuscaloosa. Nichols, Born in Bath, England, was extremely skilled in the Neoclassical and Greek Revival styles, and had first-hand experience with European architecture. The architect’s reputation had been proven with his work on North Carolina’s architecture; Nichols was an obvious choice for the statement Alabama was hoping to make. When the State of Alabama made the decision to move the state capital to Tuscaloosa, much of Tuscaloosa’s architecture at the time was colloquial and utilitarian, and the State of Alabama believed a permanent and physical expression of the Western attitude was necessary to establish successful residence in the area. An iconic structure in the Greek Revival and Federal styles was needed.[2][3]

The Alabama State House was designed as a combination of the Greek Revival and Federal styles. Nichols was greatly inspired by the architecture of the National Capitol, as well as the work of Thomas Jefferson. Nichols used Scottish architect Peter Nicholson’s designs from his 1819 ‘Architectural Dictionary’ as inspiration, specifically his plates of Henry Howard’s home, Corby Castle in England. [4]

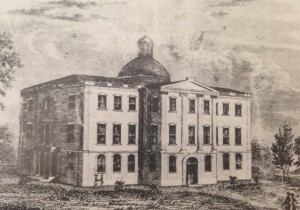

The building was commissioned in 1827, and finished in 1829. During the winter of 1828, the project’s budget was expanded from the initial $10,000 to a limit of $55,000. By the time of the Capitol Building’s completion in 1829, it had cost between $100,000 and $150,000. Childress Hill was chosen as the site of the new Capitol, so as to allow the planned copper dome to be visible from passing ships on the Black Warrior River. Alexander Baird, who would continue to do all the stonework in the entire structure, cleared the land and laid the foundation in 1827. A man named Yerby made the bricks in Northport, which were shipped over the Black Warrior River by raft. The woodwork was done by Henry Sossaman, using a whip-sawing technique.[5]

In the structure of the Greek Cruciform, the State House featured three main wings and an entrance hallway. The Supreme Court’s chamber was in the smaller west wing of the building, while the north wing contained the Senate’s chamber, and The Hall of the House of Representatives was in the south wing. Both the north wing and the south wing contained a gallery for spectators, with the south wing’s gallery being smaller than the north. The main entrance was built on the east side of the building. On the exterior, the first story is decorated with rusticated stone, with red brick siding continuing up the remaining two stories. The first story was built in heavily rusticated freestone from Tuscaloosa, while the two stories above were made of brick brought over the river from Northport. [6]

The three wings were united by a large common rotunda area, under the structure’s central dome. A lantern exists at the top of the dome in order to naturally light this central area. The symmetrical facade along with with the separation of each state legislative branch on opposite sides of the building imply an even separation of powers between the three, a reflection of the structure of American government common in the Federal style. A cornice around the perimeter of the building separates the first story from those above. Entrances at the north and south sides of the building feature one-story tall porticoes with Doric columns of sandstone, in the design of Peter Nicholson’s Corby Castle facades. The facade of the main entrance at the east side of the structure displayed two-story tall Ionic pillars, extending from the top of the first story’s rustication to the pseudo-portico atop of the building’s east side. Both the belfry and the dome on the final building were built at ground level and raised to the top of the structure, above the central 90 foot tall rotunda. The original sheathed copper dome was known to leak, and sometime before 1890 was recompleted with wood shingles.[7]

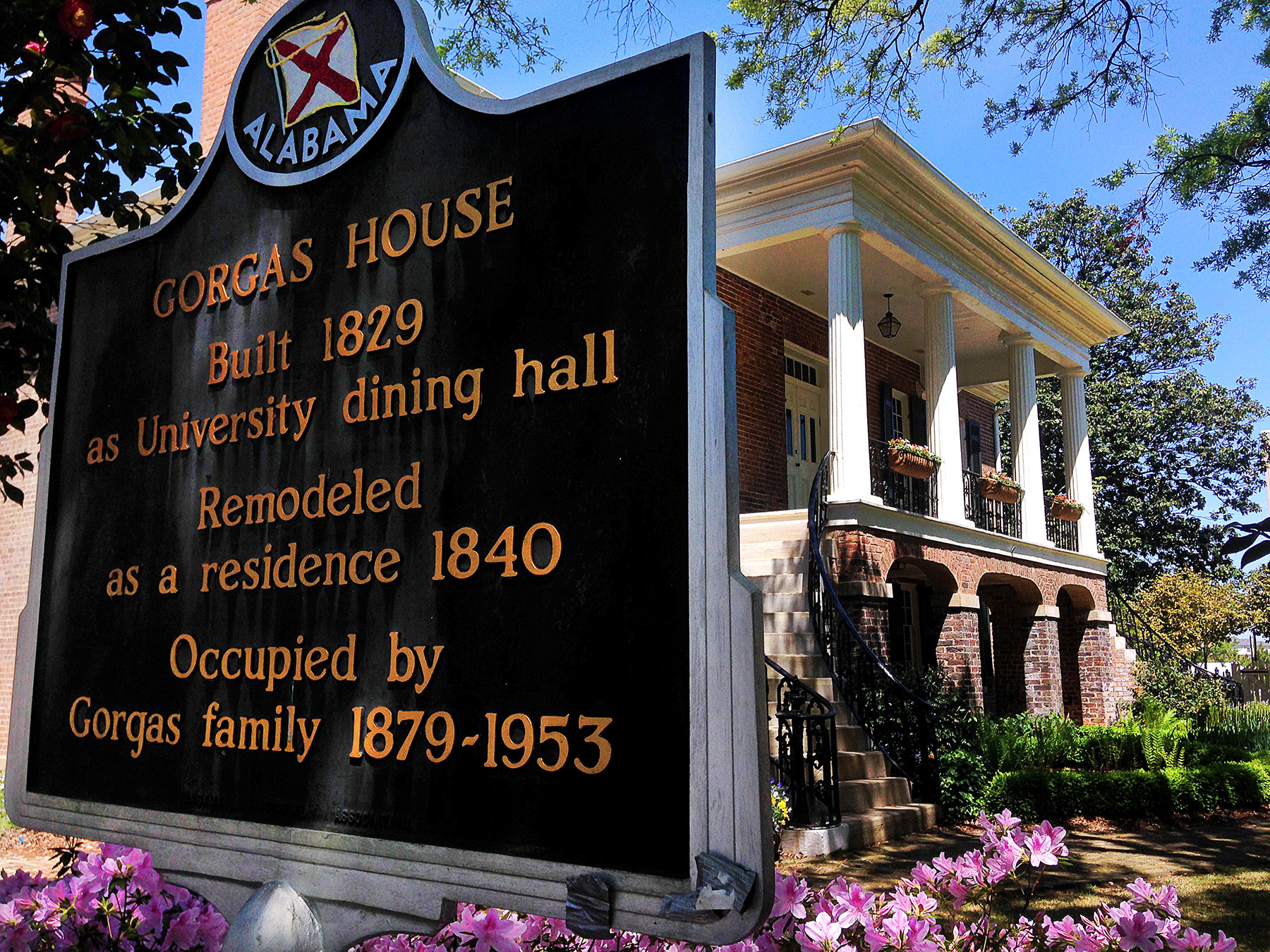

During it’s time as capital, Tuscaloosa adopted much of this style in the construction of the original University of Alabama campus, which was designed by Nichols. The impact of both the Alabama State House, as well as William Nichols, played a powerful role in changing the architectural aesthetic of Tuscaloosa from one based on agriculture to the Federal and Neoclassical influences that are still prevalent in the design of the University today. [8]

The arrival of the Neoclassical style in Tuscaloosa was highly anticipated by it’s citizens. Since the Colonial era, very few well-studied architects had designed and developed around the Tuscaloosa area. The construction of the Tuscaloosa State Capitol marked the arrival of a true Western foundation in Tuscaloosa, cementing the area as a home for Western people and philosophy. Where previously Tuscaloosa was rough and colloquial in design, Nichols anchored an elegant and humanitarian Western culture in the area through the State Capitol and his designs for the University.

During it’s time as capital, Tuscaloosa saw a great increase in immigration. The population increased from 1,500 to 4,500 between 1826 and 1846, with Alabama’s entire population nearly doubling. However, during this time a greater number of people settled in southeastern Alabama, slowly removing Tuscaloosa’s status as a central city in the state.[9] In November 1846, Montgomery was chosen as the new capitol, due to closer proximity with the majority of Alabama’s population, and a better connection to the rest of the state through the nearby Alabama River. After the state capitol was moved, the Capitol building was granted to the young University of Alabama. Seldom used by the University, the property was leased to The Baptist Convention of Alabama for the next century. In the new building, The Baptist Convention established the Alabama Central Female College, and built a four-story tall dormitory on the same land.The Representatives Hall was repurposed as a concert hall and a place for performance, while the remainder of the space was used for classrooms. The movement of the capital from Tuscaloosa to Montgomery caused economic suffering to Tuscaloosa, citizens were initially worried for their town with the loss of their place as Capitol, but with the increased success of the University of Alabama as well as the Central Female College, Tuscaloosa began to respect itself as a place of learning. In a short five years after the Capitol was moved, the population of Tuscaloosa dropped to 1,950 citizens, nearly what it was before its selection as Capitol.

In the first address of the first meeting of the State Legislation in the new Capitol in 1829, Alabama Governor Gabriel Holmes spoke of Tuscaloosa as ‘(once) a mere wilderness, the resort of savages and wild beasts only…. In the place of those humbler huts… we now behold a Capitol and a University, which when completed will be inferior to none in elegance, in taste, or in usefulness’.[10] The Chief of the Eufaula tribe spoke a farewell speech to the Western immigrants in 1831 in the very same room as Governor Holmes’ speech years earlier. ‘I come here, brothers, to see the great house of Alabama and the men who make the law… I go to the far west… we leave behind our good will to the people of Alabama who will build the great houses’.[11] In the few short years after the construction of the State Capitol in Tuscaloosa, the West had laid permanent claim to the land of Tuscaloosa County, and the Federal and Greek Revival structures were a monument to this change, celebrated by both old and new immigrants, and accepted by the overthrown natives. Tuscaloosa had succeeded in making a statement about the new type of civilization that was arriving there, one that could not be denied.

The structure was used by the Alabama Central Female College until it was burned down on August 22, 1923, speculated to be caused by faulty electrical wiring. The building was quickly destroyed, and its remains were salvaged by many of Tuscaloosa’s people for use in their own construction, bricks from the ruined capital may still be found in structures built in the early twentieth century. Both before and after its destruction, The Tuscaloosa Capitol Building was a symbol of Western culture in Alabama, not only as it once stood, but as the very bricks in the city’s growing infrastructure. Currently, the cruciform foundation remains, as well as both a segment of the central rotunda’s northern wall. Two one story-tall Doric pillars on the south side of the building mark where the entrance to the The Hall of Representatives once stood.

Though brief, the two decades of Tuscaloosa’s time as Alabama State Capitol marked the formal arrival of Western philosophy in Alabama. William Nichols’ brought Greek and Federal architecture to the area, cementing a civil and national attitude in Tuscaloosa county. Though brief, the time as Alabama’s Capitol brought prosperity that evolved into the academic and cultural self-respect Tuscaloosa has today. While the building now lies in ruins, it’s foundation remains a testament to the statement it had made, and the salvaged materials still exist in many iconic structure today. While the building itself may have come and gone, it’s impact has not been lost. The Tuscaloosa State Capitol Building will remain an icon of Western arrival in the South.

[1] Bose, Joel Campbell. Alabama history. Richmond, Atlanta etc.: B.F. Johnson Pub. Co, 1908.

[2] Peatross, C. Ford, and Robert O. Mellown. William Nichols, Architect. (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Art Gallery, 1979), 18

[3] Clinton, Matthew William. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Its Early Days, 1816-1865. (Tuscaloosa, AL: Zonta Club, 1958), 61

[4] Ford and Mellown William Nichols, 18

[5][6] Clinton Tuscaloosa, AL, 62

[7] Amaki, Amalia K. Tuscaloosa. (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2011), 21-22

[8] Brown, William Garrott, and Albert James Pickett. A history of Alabama, for use in schools: based as to its earlier parts on the work of Albert J. Pickett. (New York: University Pub. Co, 1900), 183

[9] Brewer, W. Alabama, her history, resources, war record, and public men, from 1540 to 1872. (Spartanburg, S.C.: Reprint Co., 1872) 48-49

[10][11] Ford and Mellown William Nichols, 18